Blog

Delacroix in Hong Kong: Activism, Memory and Visual Representation

Thomas Smits:

Yesterday evening World Press photo announced the winners of its 2020 contest. Nicolas Asfouri won the first prize in the General News category for his series ‘Hong Kong Unrest,’ which documents the vehement, unprecedentedly-large and long-lasting, anti-government protests in the city. Describing the first picture in the series, the World Press website notes: “A man holds a poster in Shatin, Hong Kong, as people gather to sing ‘Glory to Hong Kong’, a protest song which gained popularity in the city as an unofficial anthem.” The caption seems to be off point. While the singing protesters are barely visible and out of focus, it is the poster that the man is holding which takes center stage.

The poster is a remediation of Eugene Delacroix’s (1798-1863) painting La liberté guidant le peuple (Liberty Leading the People). Commemorating the July Revolution of 1830, which toppled the Bourbon Restoration monarchy, the image has become one of the most frequently repeated symbols of radical protest and revolutionary change. A young woman, in whom we can recognize both lady liberty and the French Marianne, leads a group of revolutionaries to freedom. Their struggle is clearly violent. While Marianne holds the revolutionary tricolore flag in one hand, she clutches a musket in the other. Other central figures swing swords and seem to shoot pistols into the air, while the entire group steps over a barricade and the bodies of fallen comrades and enemies.

As Twitter user uwu, who collects and analyzes Hong Kong protest art, notes, the poster on Asfouri’s photograph is a “veritable bingo card” of protest iconography. We see yellow hard-hats, the black bauhinia flag (the official Hong Kong flag is red) and teargas clouds. Although the connection to Delacroix’s painting is clear, the Hong Kong version turns some of its central symbolism on its head. Instead of deadly weapons, the protesters hold shields, umbrellas and, in another version, a camera, a megaphone and a laser pen. Far from violently claiming their liberty, they seem to be defending it against the direct violence of the Hong Kong police and the indirect political violence of the illiberal Chinese state.

This latest one is a veritable bingo card of all the HK protest iconography – hardhat, black bauhinia, mask, 時代革命, teargas… But note the shields, lack of weapons and the lighting – HKers see themselves as defenders of their city through the dark night, waiting for the dawn. pic.twitter.com/dgpzFhIagB

— uwu (@uwu_uwu_mo) September 24, 2019

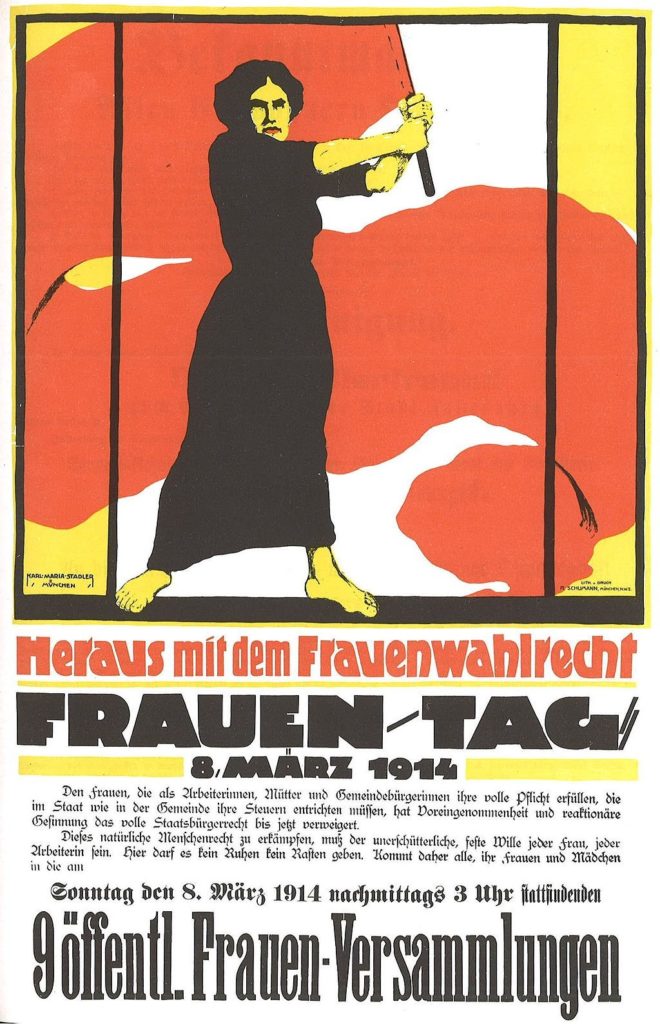

Asfouri’s picture is not the only image of the Hong Kong protests that visually quotes Delacroix’s painting. A picture in Kenji Wong’s series Hello darkness, my old friend (2019) shows three young female students, two of whom are holding a rainbow-colored Lennon Wall-inspired protest flag. In fact, the image resembles other remediations of Delacroix’s painting rather than the original. In the early years of the twentieth century, posters published during International Women’s Day often prominently featured women holding up flags. Famous examples, like Karl Maria Stadler’s Heraus mit dem Frauenwahlrecht (1914) or Adolf Strakhov’s Emancipated Woman: Build Socialism! (1926), are clearly inspired by Delacroix (read Clara Vlessing’s blog on the disputed origins of International Women’s Day). Alternatively, Wong’s photograph also bears a strong resemblance to Jean-Pierre Rey’s iconic picture of a female protester during May 68 protests in Paris, which was quickly dubbed La Marianne de Mai 68 (1968).

How Are Young Photographers Documenting the Protests in Hong Kong? https://t.co/VTfnfBwu7i

— The Click (@theclick) April 10, 2020

Asfouri and Wong’s photographs are powerful examples of the connection between activism, memory and visual representation. On the left of the poster on Asfouri’s picture, a sign contains one of the slogans of the movement: 時代革命 (Free Hong Kong, Revolution of Our Time). By remediating Delacroix’s painting, the Hong Kong protesters claim a place among a chain of revolutions in other times. From Diego Rivera’s Communeros de Paris (1928), to John Heartfield’s Die Freiheit selbst kämft in ihren Reihen (1936), to the famous la beauté est dans la rue poster (1968), to a mural on the separation barrier which runs through Bethlehem (2012), to a photograph of protesters in Gezi Park (2013), to Errin Curriers American Women Dismantling the Border III (2018).

Why does Delacroix’s painting pop up whenever people (think they) are fighting for freedom? Recently, scholars suggested that protests are essentially visual phenomena, because their political power is chiefly derived from the (symbolic) visibility of their demands in the public sphere. Only through this visibility are movements able to force other political actors, such as politicians or political parties, to acknowledge and act on their demands.

This might partly explain the games of visual telephone between social movements: by referencing and remediating successful earlier bids for visibility, they hope to improve their chances of success. While often anecdotally noticed, there is still a lot to learn about these chains of visual references and remediations. For example, where, when and why they are started, end, are interrupted, or are accelerated? Could somebody in Hong Kong be creating the next Liberty Leading the People right now?