Blog

International Women’s Day: Why is it on 8 March?

Clara Vlessing:

On 8 March, International Women’s Day (IWD), last year I marched through the streets of Amsterdam in a tide of shouting placard-wielding protestors. By planning the protest on this day, its organisers imbued it with a sense of historicity, aiming to emphasise the changes and continuities in a long-running progression of women’s marches and gender-based activism. IWD is the kind of commemoration that relies upon and reinforces a sense that your activism links you with generations who have celebrated the same day before you – what the historian Eric Hobsbawm has termed an “invented tradition”, projecting a misleading suggestion of uninterrupted continuity with the past.

Yet, I have no personal memories of IWD before the late 2010s. For someone of my generation, it feels as though the event represents some mixture of fourth wave feminism and the relentless growth of commemorative days promoted by digital media (as a result of which my Twitter feed informed me that 5 February was International Nutella Day, which fortuitously falls a good few weeks before World Oral Health Day on 20 March). Indeed, the event’s Wikipedia page suggests that annual celebrations only kicked off in 2010. But IWD has actually been celebrated by various activist groups throughout the twentieth century and mobilises a much older set of protest memories. Exactly what these memories are is, however, a point of some contention and any attempt to trace IWD’s origins takes you into a strange hall of mirrors in which commemorations look back to earlier commemorations, reflecting off each other at all sorts of angles.

In her commentary on “The Socialist Origins of International Women’s Day” Temma Kaplan lays out two rival origin stories. The first stems from a strike by women textile workers in New York on 8 March 1857 and the celebration of the anniversary of that event in 1907. Although this date has been regularly accepted as the first IWD, there does not seem to be any evidence that the original strike or its anniversary celebration fifty years later actually happened. Instead it appears that this narrative was invented in France in the 1950s, with the choice of 1857 based on the birth year of the prominent German Marxist Clara Zetkin (1857-1933).

The second story is messier, with shifting versions of exactly which events early IWDs commemorated. American Socialists held a National Women’s Day on 23 February 1909 in New York. Then, in a meeting of the Second International in 1910, Zetkin proposed a day for women workers similar to the recently-established May Day. In 1911 socialist groups around Europe celebrated what is claimed to be the first IWD on a day that is variously described as marking the fortieth anniversary of the Paris Commune (18 March) or attributed to the commemoration of the 1848 revolution in Berlin (19 March). However, the defining moment in the celebration of IWD took place in Russia in 1917, when Bolshevik women took to the streets on strike, demanding better living conditions and an end to Tsarism, in an event that precipitated the February Revolution. These women took their lead from the American celebration of IWD on 23 February in the Gregorian calendar, which was 8 March in the West. After the end of the First World War, Zetkin (now a Communist) worked with Lenin to set up the day as a Communist holiday. To this day, it remains a national holiday in most Communist and ex-Communist countries.

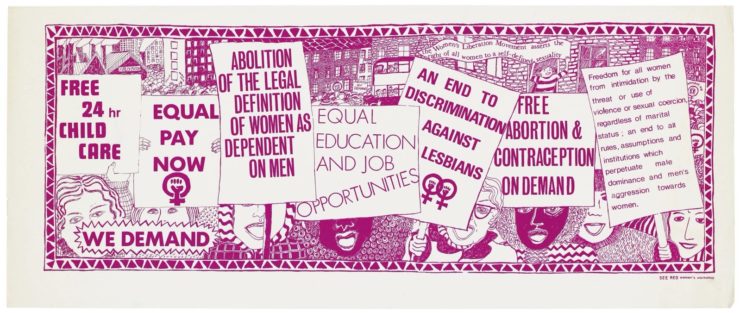

Kaplan suggests that the first of these stories – of the New York strike – was invented in order to distract from the actual origins of the day in Soviet History and Bolshevism, making it more palatable to later generations of feminists. This mythical story seems to have risen in prominence in the late 1960s when IWD was revived as a tradition by women’s groups in the United States and subsequently picked up internationally by radical feminist groups. The celebration of the day by feminists reportedly troubled communist women, who saw it as a corruption of the day’s true meaning. In this way, the rival stories demonstrate a conflict that runs throughout my own research on the cultural memory of women activists: between those groups that view women’s activism as relevant to all women and those who see it as inextricably linked to class-based activism or even view women’s liberation as secondary to class liberation. Zetkin herself fell firmly into this second group. Her sympathies were with working women and she viewed feminism as a distraction from the real struggle for the middle and upper classes.

The complex backstory to this event demonstrates that the narratives we receive about the past are always partial, fragmented, constructed and tend to reveal more about the present than they do about what ‘actually’ happened. IWD has long exceeded and overlooked its radical origins, standing as much as a chance for people to share stories about the women in their lives, or as a sales opportunity, as it does a call to protest. Ostensibly you can pick whichever origin story you please – or make up a new one. But whatever you do, spare a thought for the hope and revolutionary fervour of the women who first celebrated this date. Whichever date it might have been.