Blog

Remixing the Past: The Soundtrack to Black Lives Matter

Marit van de Warenburg:

The Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests that shook up both sides of the Atlantic last summer, in the aftermath of the killing of George Floyd by Minneapolis police officers, were infused by music. In the United States, songs such as Anderson.Paak’s “Lockdown” and H.E.R.’s “I Can’t Breathe” sought to capture the anger, but also the hope, that drove the BLM movement. The Dutch branch of the movement was supported by artists such as Akwasi and Bizzey, as well as the hip hop-project #Adembenemend (#Breathtaking – alluding to George Floyd’s final words) – an online song chain instigated by rapper Manu, record label Top Notch and research institute The Black Archives which invited artists to address their personal experiences of racism over a publicly available beat. In their protest songs, artists across the globe created musical memoryscapes which placed the 2020 protest within longer, historical struggles and moved beyond nationally specific approaches to the past.

Although the content of the Dutch songs and the American ones varied considerably, their overarching message was the same: racism and violence has to end. As much as songs supporting the BLM movement were used to urgently address the present, they also remediated past events. Some artists placed their newly produced tracks in a wider framework of historical oppression and resistance, while others also placed themselves in past traditions by reworking protest songs such as Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit” (1939), Nina Simone’s “Mississippi Goddam” (1964) and N.W.A.’s “Fuck tha Police” (1988).

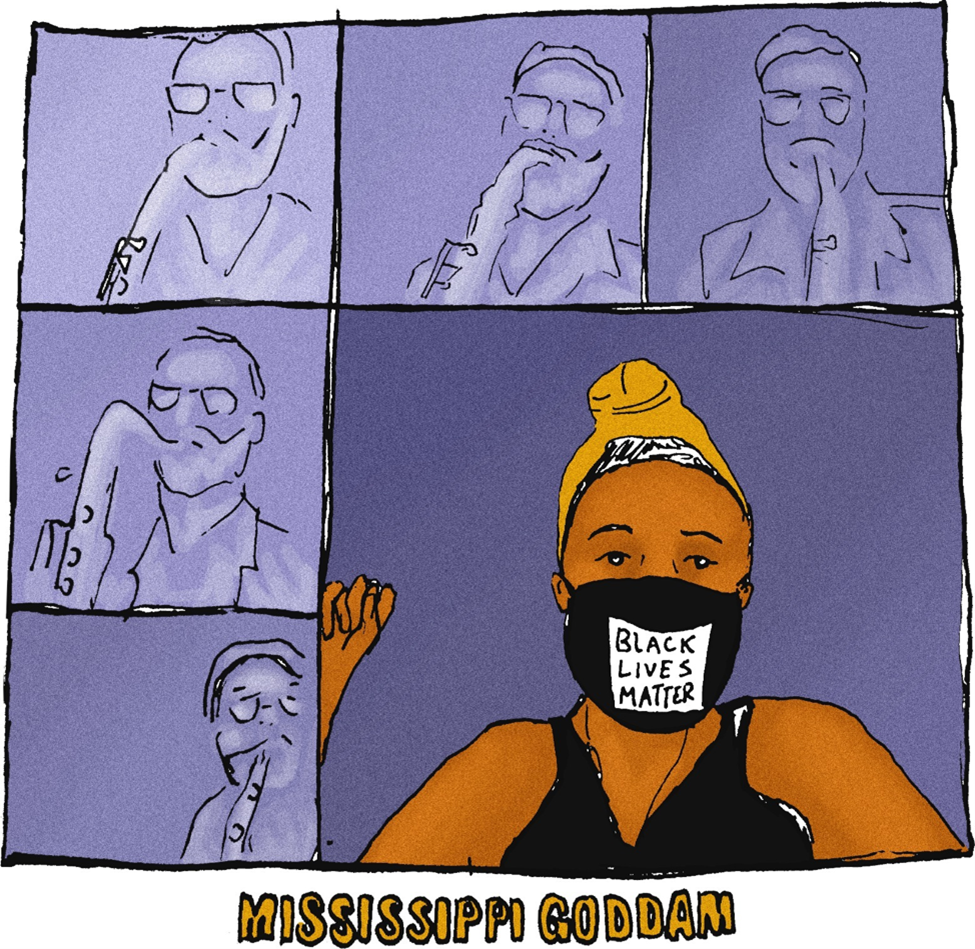

Mississippi Goddam

Illustration Marit van de Warenburg (coloring Thomas van Gaalen), 2021.

Particularly Simone’s song, written in response to racist lynchings carried out in Alabama and Mississippi in the 1960s, was performed and quoted in support for BLM, and stood at the forefront of its digital protest. “Mississippi Goddam” was recalled at demonstrations and in videos both in Europe and the United States, and aside from some localized variants (e.g. “Roffa [slang for Rotterdam] Goddam” and “Minnesota Goddam”), the lyrics to Simone’s anthem remained largely unaltered. The footage accompanying some of the online covers, however, does explicitly highlight the continuity of Simone’s message: singer Lydia Harrell raises her fist and puts on a face mask saying “Black Lives Matter” as saxophone player Jared Sims starts playing a solo to Simone’s cynical show tune. The song itself reminds listeners of the long history of struggles for black emancipation and re-using it in a contemporary context (in some cases with contemporary attributes such as face masks or textual changes that address more recent issues) calls for a comparison between the 1960s and 2020. It also calls for a spatial comparison: the widespread international use of the song links local BLM branches to a greater, transnational struggle.

I Can’t Breathe.

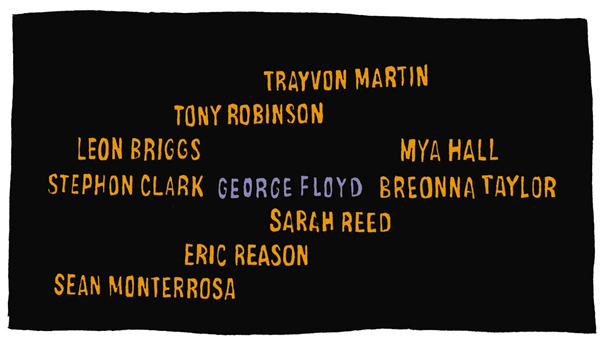

Illustration Marit van de Warenburg (coloring Thomas van Gaalen), 2021.

Newly written songs, however, also seem to invite historical comparisons. H.E.R.’s “I Can’t Breathe,” released in June of 2020 is accompanied by a video showing BLM protests around the world. Halfway through the song, just as the artist starts rapping, George Floyd’s name appears in the middle of a black screen. Over the course of ninety seconds, the screen is filled with about two-hundred names, making the video a monument to the memory of recent victims of police violence in the United States.

Through the song’s lyrics, these names are linked to a longer history of violence:

Trying times all the time

Destruction of minds, bodies, and human rights

Stripped of bloodlines, whipped and confined

This is the American pride

It’s justifying a genocide

Romanticizing the theft and bloodshed

That made America the land of the free

To take a black life, land of the free

To bring a gun to a peaceful fight for civil rights

You are desensitized to pulling triggers on innocent lives

Because that’s how we got here in the first place

The song not only places contemporary police violence next to slavery (“stripped of bloodlines, whipped and confined”—a phrase sharply juxtaposed with the visual insistence on remembering the names of African Americans who have been killed), it also connects America’s foundation to a long history of oppression. H.E.R. explicitly positions herself in a longer tradition of protest music. “The revolution is not televised / Media perception is forced down the throats of closed minds” she raps, referencing Gill Scott-Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” the title of which was popularized in the 1960s as a slogan among American Black Power movements. H.E.R. also re-uses Holiday’s legendary “Strange Fruit”: “That kind of uncomfortable conversation / Is too hard for your trust-fund pockets to swallow / To swallow the strange fruit hanging from my family tree.” Here, she not only insists on remembering lynchings, she also remembers Holiday’s resistance to those lynchings; a remediation which underscores the long-term and structural nature of racism and police violence in the United States

Black Lives Matter in the Netherlands.

Illustration Marit van de Warenburg (coloring Thomas van Gaalen), 2021.

In the Netherlands, in a similar – yet contextually different – vein, the songs in the #Adembenemend-chain, remember a wide range of histories. One artist rapping to the #Adembenemend-beat addresses the daily racism experienced by his children and the rise of far-right politics in America and Europe. But the song also covers the struggle for Indonesian independence, the Dutch slave trade and the controversial figure of Zwarte Piet, the Dutch folkloristic character, known for wearing blackface. By remembering these varied subjects in his lyrics and by musically stringing them together in response to the Black Lives Matter movement, Manu creates a new story about the past that critically addresses dominant outlooks on Dutch history and highlights the multiple factors that constitute systemic racism in the Netherlands.

While covering Simone or Holiday supports, and perhaps legitimizes, contemporary protests by placing them in tandem with stories of the past (specifically the memory of the Civil Rights Movement), #Adembenemend and “I Can’t Breathe” explicitly break down the space and time between such stories. By setting them to the same beat and melodies, these various stories are explicitly connected as well as given equal weight and significance. It shows how music can function as a carrier of memory: it revitalizes the past either by re-using older songs or by lyrically commemorating earlier struggles. Through the format of a single song with more or less consistent musical qualities, then, a range of memories are brought together, thus forming a new narrative to support contemporary activism.

***

Marit van de Warenburg was an intern for ReAct September 2020-February 2021. She is currently writing a research master’s thesis on protest music. Special thanks to Thomas van Gaalen for his insights and help with the illustrations.