Blog

The Contentious Subject Speaks

Duygu Erbil & Clara Vlessing

This blog draws from a presentation we gave as part of ReAct’s recent conference on “Remembering Contentious Lives”.

Speeches and speaking have long been essential to contentious politics. While oratory practices are shared across different repertoires of contention, the ideal of the freedom of speech has been an underlining principle for all contentious politics. Especially in the United States, where the first amendment establishes free speech as a legal opportunity and a cause for social movements, the model of the political speaker has taken a central place in the cultural memory of contentious acts and actors. From the soapboxing Wobblies and their free speech fights against the capitalist class, to the New Left associated Berkeley Free Speech Movement, the speaking model of radical political subject overcomes any division between deeds and words. This is perhaps why the title format [The Contentious Subject] Speaks is a trend in radical publications in English, especially in the U.S. Often entitling collections of political speeches in book form [The Contentious Subject] Speaks has been a trend since the 1960s-1970s, providing the title for numerous books that posthumously deliver the performed speech in print form.

This trope framed political speech as autobiographical, positioning it as the “true story” of a revolutionary life told by the revolutionaries themselves. Often, the framing of [The Contentious Subject] Speaks claimed to bring a revolutionary back to life, so that they might address themselves to an audience. Today, we still see the echoes of this trope and its function in narrating revolutionary lives. The 2022 publication of Anne Braden Speaks by NYU Press is framed to “correct” the “distorted narrative” of the revolutionary’s life and politics. John Brown Speaks, a series of performances by Kerry Altenbernd who presents first-person narratives of John Brown’s life, claims to “bring the abolitionist to life”. The tradition of [The Contentious Subject] Speaks as a title format marks an intriguing genre of political address reframed by editors and publishers as revolutionary life narrative.

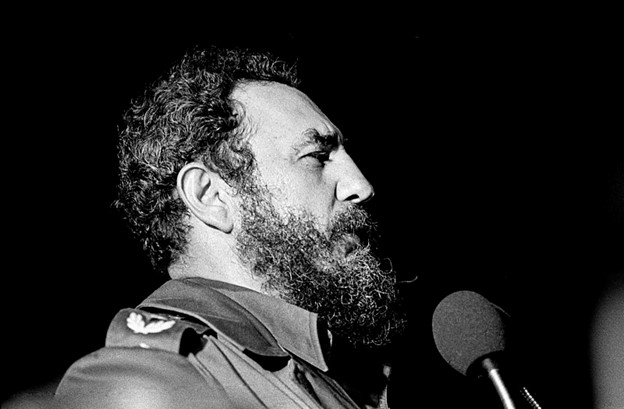

From the 1960s onward and in conjunction with the Cold War, radical publishing houses started to salvage the speeches of censored and discredited revolutionaries to let them speak for themselves, with the idea that speech discloses the true identity of these historical figures. Published in 1965, Malcom X Speaks, a collection of speeches edited by George Breitman, aimed to “correct, at least partially, some misconceptions about one of the most misunderstood and misrepresented men of our time”. Two years later, Che Guevara Speaks, aimed to “provide a faithful reflection of Che as he was, or, better, as he developed”. Or, when Fidel Castro Speaks was published in 1969, it set out to show that: “Fidel differs from other revolutionary heroes […] Whereas Lenin, Trotsky, Debray, Fanon, and Ho most often wrote for party cadre […] Castro invariably addresses himself to the masses of the Cuban people.” In these examples, the democratic and unifying qualities of political speech are favourably compared to characterisations of theoretical writing as elitist or divisive. The speakers offer themselves to the people.

At times – as in the 1970 introduction to Rosa Luxemburg Speaks – these collections can compete with other forms of life writing. They “tell the life story” of these revolutionaries “in their own words” and so are able to reveal “more about them than any biography could”. The addressee of [The Contentious Subject] Speaks overcomes the misunderstandings surrounding Malcolm X, sees how Che develops as a young revolutionary, encounters Fidel as a teacher and not a demagogue. The suggestion that speech reveals the “true” representation of a self, situates the speaker as an autobiographical subject. These speakers often move from being producers of revolutionary discourse to becoming political celebrities.

Indeed in the introduction to the third edition of her collection Red Emma Speaks: An Emma Goldman Reader Alix Kates Shulman describes Emma Goldman as “[A] role model and exemplar, as a stunning speaker, a star, […] an anarchist leader of immense energy and integrity”. The book demonstrates Goldman’s extensive posthumous celebrification; her speeches and essays are treated as biographical information that might contribute to a blueprint of how to live a feminist life.

Despite the apparent immediacy of the [The Contentious Subject] Speaks format – with its suggestion that the subject’s voice is unmediated and neutral – Shulman’s presence as, what scholars of life writing would call, a “coaxer” is unavoidable. Throughout Goldman’s words are heavily annotated by Shulman’s. Each section includes Shulman’s introduction to the various speeches and lectures they collate, drawing from Goldman’s own publications and from public archives. Stressing the directness of Goldman’s address, Shulman accounts for her own involvement in practical terms: “…the essays, magazine pieces, pamphlets and speeches […] collected here speak for themselves. I have divided the writings into four sections”. The immediacy with which she moves from promoting the unmediated nature of Goldman’s speech to explaining her own role in selecting, arranging, and categorizing , demonstrates her sense of proximity to Goldman, and promotes the idea that the two have a close interpersonal relationship.

In Red Emma Speaks, first-person discourse has a mobilising potential: Goldman’s life is submitted as example to Shulman’s fellow radical feminists. In line with the present tense of its title the text pulls Goldman into the here and now of Shulman’s political moment. Her focus on providing access to the intricate relationship between Goldman’s ideas and her life narrative is both product and productive of Goldman’s growing celebrity over the course of the late twentieth century.

In the same Cold War era, but this time in Turkey, the Marxist-Leninist revolutionary Deniz Gezmiş – who had been executed by the state in 1972 – was likewise conjured up to speak for himself in Erdal Öz’s Deniz Gezmiş Anlatıyor [Deniz Gezmiş Recounts or Deniz Gezmiş Speaks], four years after Gezmiş’ death. Like other commemorative books from this decade, it is a collection of legal documents and expert testimonies about the trial and the execution, but unusually it includes a ventriloquized interview with Gezmiş that gives the book its title. The interview was conducted in prison, where the author Erdal Öz was incarcerated at the same time as Gezmiş. It is the only account of Deniz Gezmiş narrating his own story, aside from his court speech. Öz’s ventriloquized interview was filling a gap, and his paratextual framings introduce the book as the story of Deniz Gezmiş told in his own voice.

As in the case of Shulman and Goldman, Öz’s co-production of Gezmiş’s life narrative is framed to suggest that it offers a glimpse of Gezmiş’ “inner life”. Öz insists that Gezmiş speaks through him, emphasises Gezmiş’ position as narrating subject and asserts that the interview is in Gezmiş’ “own voice”, even though it is based on illegible notes that Öz took in prison and which were smuggled out five years before the time of writing. Like in the American examples, the speaking revolutionary ceases to be solely the agent of political discourse and addresses himself and his life story to readers who might had misunderstood him.

[The Contentious Subject] Speaks appears to reveal the “true” identity of the speaking agent and remains to frame revolutionary life narratives. Taking up subject positions as the intimate interlocutor or confidant, coaxers like Shulman and Öz construct the idea that by recollecting Goldman and Gezmiş’ speech we – the addressees, of the private book but not the public speech – might be brought into direct contact with them and learn something fundamental about their lives. In a Cold War context, the agent of revolutionary discourse is transformed by intermediaries, who frame speech and political address as self-presentation. In these framings, political address discloses stories of revolutionary lives and brings the addressees into intimate relationships with the speakers. This casts new light on the role of editing and publishing in mobilisation.