Blog

Using Memory: The anti-colonial periodical Indonesia Merdeka (1923-1933)

Anna Stibbe:

That Indonesia and the Netherlands share history is a well-known fact, but this history has been told in a completely different way on each side. The recent commotion around the term Bersiap – used only in the Netherlands to indicate the period of extreme violence in Indonesia in 1945-1946 – made this painfully clear. But it is not only the colonial past in Indonesia, but also Dutch national history, that have been remembered differently by these groups.

The colonial past has long been remembered in a positive light in the Netherlands. In a 2020 YouGov-survey, half of the Dutch respondents confirmed their continuing sense of pride in their country’s colonial history. But the realisation that this past can be seen from an entirely different perspective, that colonialism was also a time of extreme poverty, exploitation and enslavement, is starting to seep into Dutch institutional awareness. Last January, Dutch newspaper De Volkskrant published the results of a survey set up with the Indonesian history website Historia, asking Indonesians how they view their country’s history of colonisation. One respondent stated: “the VOC [the Dutch East India Company – who laid the foundation of the Dutch empire in the Indonesian archipelago in the seventeenth century] introduced corruption; the colonial administration brought exploitation and racism.” Another said: “we were slaves within our own country.” Their language could not be any clearer about the harmful legacy of colonialism.

This understanding of the past is not new: it has been promoted by Indonesians in the Netherlands since before WWII. Members of the Perhimpoenan Indonesia (PI), a nationalist association for Indonesian students in the Netherlands that was established in 1908, anonymously penned their perspective on history in the periodical Indonesia Merdeka (published in Dutch under this name from 1924-1933). The anti-colonial activists who wrote this periodical used memory for their political aims. In Indonesia Merdeka, the period of Dutch colonial rule is framed as 300 years of oppression and exploitation during which Indonesians lived a miserable existence. The Indonesian struggle for independence is presented as the logical consequence of this untenable situation. The views circulated by the PI were very influential in the Indonesian nationalist movement and many of the association’s former members would become Indonesia’s future leaders.

Throughout Indonesia Merdeka, memories of Indonesian resistance are championed. These are presented as proof that the burning longing for freedom in the hearts of the Indonesian people could never be fully extinguished. For instance, Javanese prince Diponegoro (1785-1855) is put forward as national hero par excellence. He fought the Dutch during the Java War (1825-1830), which Indonesians call the Diponegoro War. In one 1924 article of Indonesia Merdeka, he is recalled as one of “our martyrs, our heroes” that “our hearts should commemorate”. In the Netherlands, the prince is barely remembered.

Conveniently for the PI, the Dutch also had a proud history of resistance against a foreign oppressor. During the Dutch Revolt (1568-1648), the Dutch fought off the Spanish from their territory. The saga of this struggle has been crucial in the construction of Dutch national identity. In Indonesia Merdeka, this history of Dutch resistance is used to expose their hypocrisy. One article of the periodical describes how Indonesian students who learned about Dutch freedom heroes could not help but think about their own heroes who had wanted exactly the same thing: “to free their country from the foreign yoke”.

Time and again in Indonesia Merdeka, the history of the Dutch Revolt is ironically referenced, especially when the Indonesian nationalists wanted to refute Dutch arguments against them. When the Dutch criticise the use of the name Indonesia instead of the Dutch East Indies, the writers ask: “did the Dutchman also speak of a Spanish Netherlands, when Philip II still had power over this country?” When the Dutch say that Indonesia is not yet ‘ripe’ to govern itself, the question comes up: “did the Dutch have to wait until Spain declared them ‘ripe’ to become independent, or did they take up their arms to force their independence from Spain?” When the Dutch declared that Indonesian non-cooperation is ineffective, one of Indonesia Merdeka’s authors wonders if they even know their own national history, since they also used non-cooperation in their struggle against the Spanish.

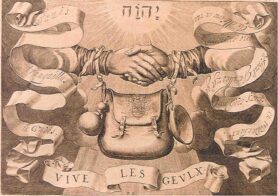

One of Indonesia Merdeka’s articles explains how opposing forces in any conflict try to make the other party look bad: “the Dutch must remember the once humiliating ce ne sont que des gueux”. (The Dutch noblemen who revolted against Spanish rule were once called gueux or ‘beggars’: not people to be taken seriously. But the Dutch adopted this name, calling themselves ‘geuzen’, and proving themselves to be a serious threat after all.) In a 1925 interview with the Dutch newspaper Indische Post, Minister of Colonial Affairs Simon de Graaff called members of PI kwajongens, or ‘naughty boys’. Subsequently this qualification is frequently recalled in Indonesia Merdeka.

Traditional emblem of the Dutch ‘geuzen’. c. 1626, Pieter Serwouters, Nederlandtsche Gedenck-clanck.

For example, a 1925 article reporting on Dutch attempts to stop issues of the periodical from spreading in the archipelago because of its incendiary content notes that “one does the kwajongens too much credit, gentlemen, by considering their writings as dangerous to the state.” When in 1927 the Dutch police searched the houses of PI members in Leiden and The Hague and confiscated many documents, the article in Indonesia Merdeka reporting on these events opens “ils ne sont que des gamins”: they are only boys, or kwajongens. A clever play with words, that strengthens the historical analogy of the Indonesian nationalist movement to the Dutch Revolt.

While much of the Dutch public sphere has only relatively recently considered an Indonesian take on history (as shown by initiatives such as the De Volkskrant and Historia survey) the periodical Indonesia Merdeka provides evidence that already in the 1920s and 1930s Indonesian views were published in the Netherlands. The authors of Indonesia Merdeka used the memory of both Indonesian and Dutch resistance. Celebrating figures such as Diponegoro strengthened a resistant collective identity of Indonesians, while cleverly subverting the history of the Dutch Revolt undermined Dutch colonial claims. This shows how already before WWII, Indonesian anti-colonial activists in the Netherlands propagated their version of the past to legitimise their political pursuits in the present and imagine the future they longed for so strongly – a future when Indonesia would be free.

***

Anna Stibbe was an intern for ReACT from September 2021 to February 2022. As a Research Masters student in History, she will continue her research on Indonesian anti-colonial thought while writing her thesis.