Blog

Colour: Remembrance as Resistance

Ann Rigney:

A former municipal swimming pool in the Belgian city of Liège is now home to a museum called the Cité Miroir, dedicated to “citizenship, memory, and intercultural dialogue”. On permanent display is an exhibition devoted to the memory of struggles for social justice and workers’ rights in this heavily industrialized province. The catalogue to the exhibition, aptly titled A la conquête de nos droits [Towards Achieving our Rights], includes a painting called “L’assassinat de Tayenne à Roux” [“The Murder of Tayenne at Roux”]. It was made in 1951 by an artist collective called Forces murales, dedicated to renewing public art in the post-war years through the production of giant wall tapestries and murals which would also offer employment to craftsmen. The images, in the spirit of Mexican muralism, were intended to speak to the working classes by honouring their labour as well as their victories and hopes, but in an artistically innovative way that didn’t fall back into the clichés of socialist realism.

Assassinat de Tayenne à Roux en 1932. 1951, Forces murales (L. Deltour, E. Dubrunfaut, R. Somville). Coll. IHOES. Reproduced with permission.

In 1951, Forces murales created a series of large paintings intended for use as portable murals marking out the history of the workers’ movement in Belgium. Of the nine sites of memory that were visualized, three entailed incidents in which activists were killed by the police. The one reproduced here pertains to the death of a 20-year-old Belgian miner called Louis Tayenne who was killed during a strike for better working conditions at the height of the Depression in 1932. A grim topic from grim times. We see the supine figure of Tayenne and, around him, his fleeing comrades. The two flags are positioned to form a V, marking a central line dividing the dead man on the lower left-hand corner from the small crowd in the top right. Beyond the symbolism and the dynamic composition, however, the overwhelming impression is of movement and colour. The colour red, steeped in the memory of revolution, is very prominent in the two flags and the woman’s dress. But here it takes the form of a soft scarlet in combination with yellows, browns, and blues.

Ever since I encountered it, this painting has puzzled me. Why should the memory of activism crystallize around police violence? And how to make sense of this lavish use of colour?

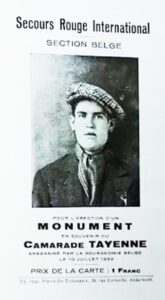

Tayenne’s death in 1932 was first documented in black and white. Soon after his death, he became the subject of a memory cult: the place of his death was marked by graffiti, a gravestone was erected noting that he had died “defending the working class” and his black and white photo-portrait came into circulation.

On the first anniversary of his death, a huge rally was organised by the Belgian Communist Party which brought 10,000 workers onto the streets of Roux. We know about this thanks to a documentary made by Jean Fonteyne and Albert van Ommeslaghe called Manifestation pour Tayenne (1933): a black and white silent film which begins at the spot where Tayenne was killed and then goes on to show a banner-waving crowd marching through the town to the graveyard (the flags are presumably coloured red but we see them in greyscale). It is clear from the many clenched fist raised in salute and the impassioned speeches (appearing all the more impassioned because they are soundless) that the occasion was used not just to commemorate the dead man but also to continue the fight for workers’ rights. In this way, remembrance became resistant and, as such, a vector of hope. It acknowledged the fact of state violence while also refusing to accept it as the ‘last word’.

Manifestation pour Tayenne. 1933, dir. Jean Fonteyne, Albert van Ommeslaghe. Public domain.

Resistant remembrance exemplifies a specific form of memory activism. It is ‘resistant’ because it seeks, not just to recall the past, but to intervene in the present. The memory cult around Tayenne, including the documentary, reflects a long tradition of left-wing martyrology. The idea of martyrdom provided a ready-made and historically rooted model for making sense of the death of individual protesters by linking it to the act of bearing witness. As the documentary shows, remembering Tayenne’s death ‘in action’ gave his comrades an occasion to publicly bear witness once again to workers’ oppression and the need to bring about change. The killing of a peaceful activist adds an extra dimension to activists’ demands (Gene Sharp called this a form of political jiu-jitsu where the strength of the regime is used against it). Calls for the killers to be held accountable amplify original calls for social transformation and also, crucially, produce a new reason to take to the streets – in the immediate aftermath of the killing, but also in the mode of pre-planned processions on anniversaries.

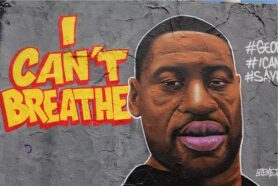

Resistant remembrance is most obvious when it takes the form of a public demonstration. But it can also play out through the cultural artefacts that carry memory, particularly images. Carried on t-shirts or displayed on public walls, images become active forces in shaping the memory and hence long-term impact of an event. The iconic portrait of George Floyd offers a case in point. Although Floyd was not ‘killed in action’ as a demonstrator, his image spread from city to city in the form of a mural based on a photograph taken when he was alive that mobilised people against systemic racism. These murals operated in the mode of accusation (this man should not have been killed) but also in the mode of defiance (he is still a presence).

Images thus trigger recollection and shape how the past is recalled in public. They are not just conduits of information. More importantly, as visual artefacts they also have a performative force in the present. Even when they refer to the destruction of life, they themselves have a capacity to generate energy, affect, and new forms of attachment in the here and now. The name “Forces murales” was presumably designed to capture this fact.

Which brings me back to the question of colour. The huge painting of the death of Tayenne, while recording the death of a young man, also reaffirmed – and continues to reaffirm – the value of life. It does so in its depiction of movement and, above all, though its colour. The bright scarlet flags – but also the yellow trousers and waistcoat, the blue of the sky – work as a counterweight to the off-stage violence. In short: images are not merely carriers of memory. They are also agents of memory activism. In their colour and composition, and the pleasures these provoke, they remember the past while also taking a stand against history and against violence.