Blog

Trans Memory Activism and Visibility: Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina

Daniele Salerno:

The Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina represents a group of trans activists who collect, organize, and circulate photographs and written materials (diaries, letters, postcards) about trans people in Argentina, with a focus on visual archiving. In 2020, in collaboration with Editorial Chaco, this group published an eponymous selection of photos and archival materials alongside short autobiographical texts. After the celebration of the International Trans Day of Visibility (March 31), a reflection on the Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina’s book may help us to see the relationship between cultural memory, visuality, and social movements in the specific case of trans activism.

Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina, Editorial Chaco, 2020.

The archive dates back to the 2000s when the trans activist Claudia Pía Baudracco started to collect private pictures of friends and activists with the long-term project of building a trans archive. In 2012, Baudracco died and one of her friend, the activist María Belen Correa, opened a private Facebook group asking trans people in Argentina and abroad to join and share their private memories and pictures. Since 2014, with the support of the photographers Cecilia Estalles and Cecilia Saurí, the collection has been gradually transformed into an archive. In 2017, the Cultural Center of Memory Haroldo Conti in Buenos Aires – one of the most important Argentine memory institutions – hosted an Archivo de la Memoria Trans exhibition titled Esta se fué, a esta la mataron, esta murió [this one left, this one was killed, this one died]. Held in an important site for the symbolic and physical memory of post-dictatorship Argentina, the exhibition was the first public recognition of the trans archive.

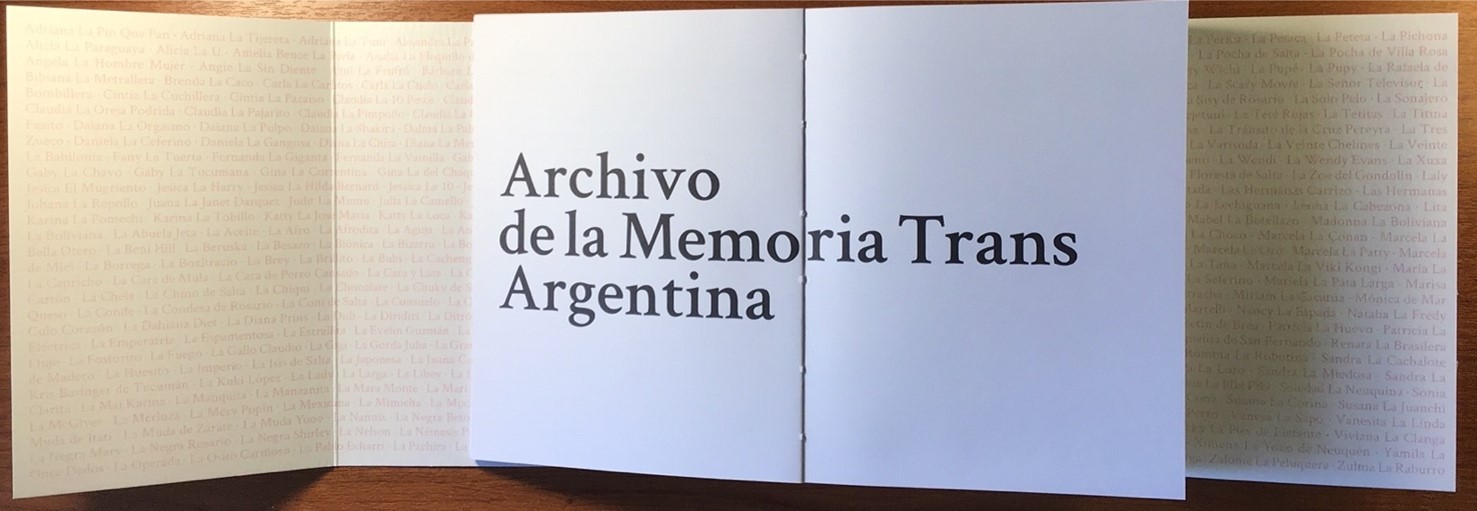

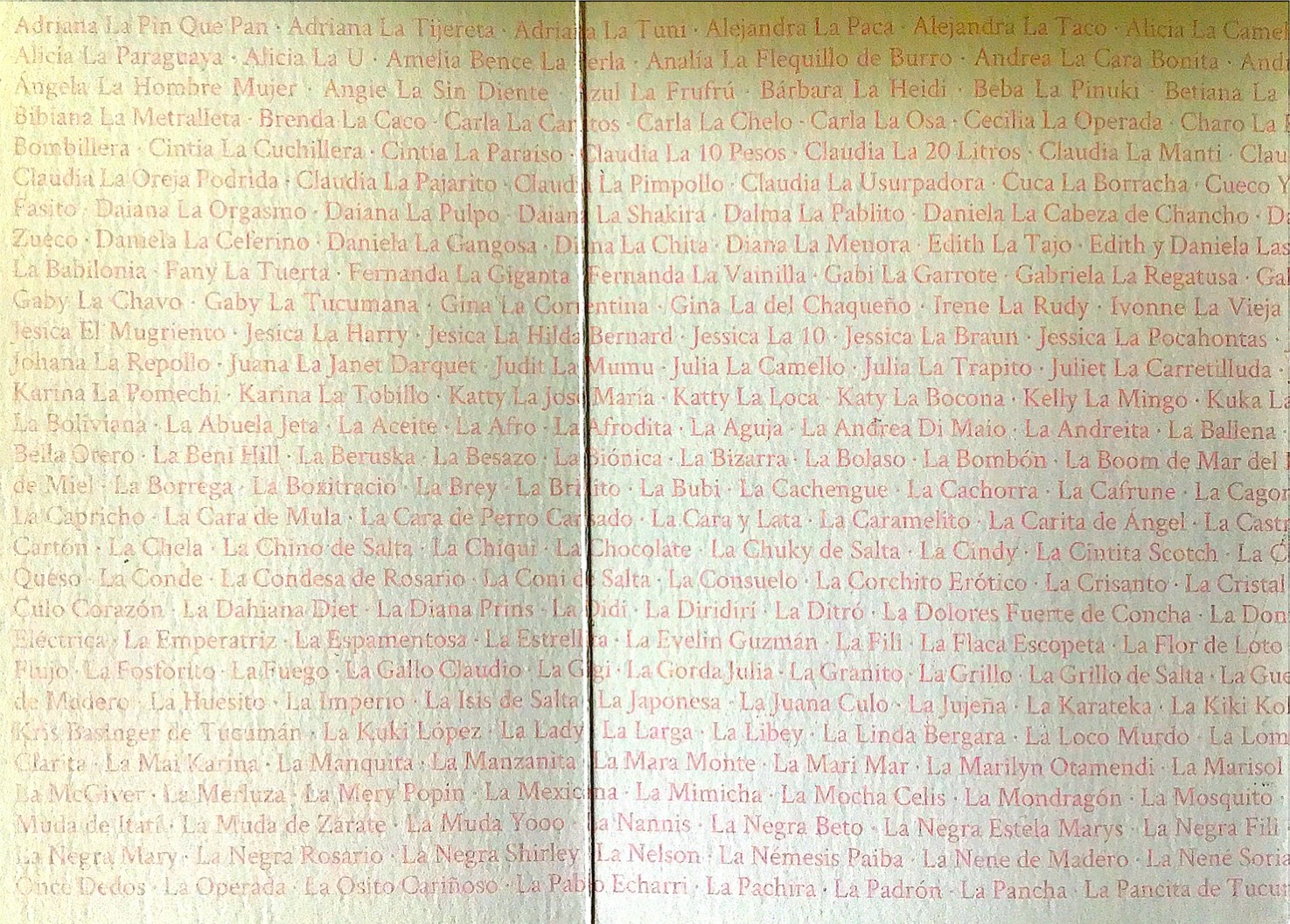

Unfolded cover flaps with names from the Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina book.

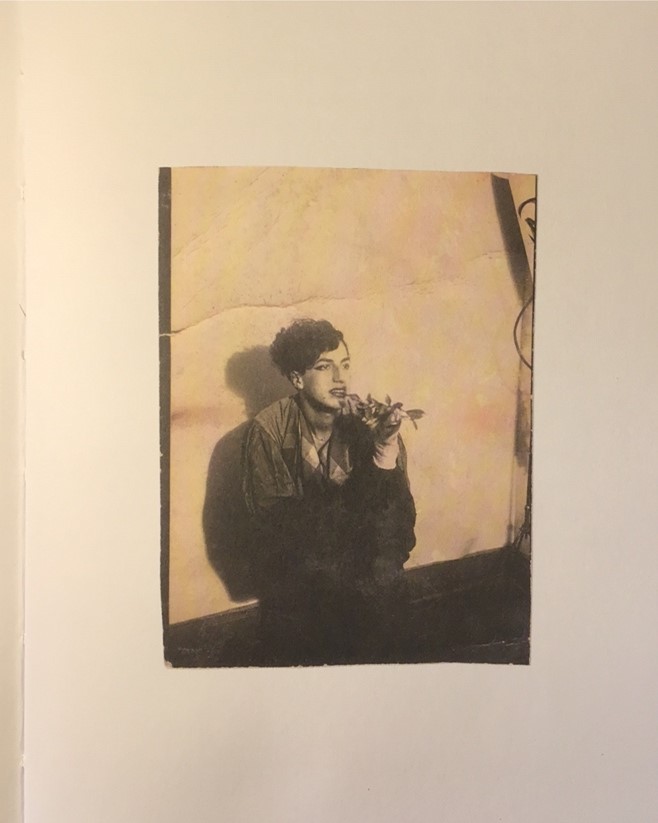

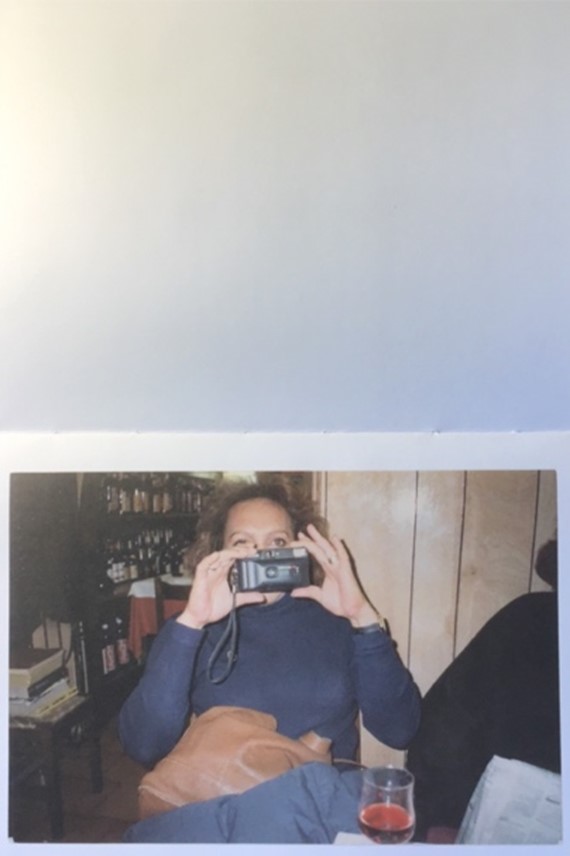

The three first pages of the 2020 Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina demonstrate how the trans collective (re)position themselves as narrators. On opening the book, we find a black and white picture of a woman in profile against a white background. A short text follows, where a first-person and anonymous narrator describes the many meanings of the act of taking pictures in the daily life of a trans person. Turning the page, we see a woman who is taking a picture in the mirror. This sequence seems to use visual narration to depict a transformation in trans subjectivity: from portrait to self-portrait via a first-person account, the trans subject is repositioned from being the object of the gaze to providing the gaze that frames and organizes. This is the philosophy which underpins the trans archive, one which promotes the narration of trans memory in the first person.

Image from the Malva Solía fonds, included in Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina.

Image from the Carla Pericles fonds, included in Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina.

The book is framed by two cover flaps that, unfolded, present a list of names and nicknames. The focus on names and naming has a close connection to activist causes in post-dictatorship Argentina, in terms both of the right to identity and the right to memory. Disappearance as a practice of repression was the notorious trademark of the last Argentine dictatorship and, in general, of the dictatorships in the Southern Cone under the US-backed campaign “Operation Condor”. It entailed the systematic violation of the right to be remembered for the 30,000 disappeared and the right to identity – the right to a name, to family relationships, to public records – for the estimated 500 children born while their mothers were in captivity and ‘appropriated’ illegally, by perpetrators and their families. Human rights activists have collected information in order to reconstruct the biography of individual victims and to find the children, now adults, of the disappeared, who have lived their lives ignorant of the truth about their parents and their own real names. The mission of many activists, and now of the state, is to find these children so as to give them their original name and the story of their parents. Archives, databases, monuments, textual and artistic artefacts and commemorative occasions (like the National Day for the Right to Identity, on October 22) have been created with this purpose. One device for such acts of remembrance is the listing of names, as epitomized by the walls of the Parque de la Memoria where the names of the disappeared are engraved.

The Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina appropriates and resignifies the practice of listing name for another cause: to claim and celebrate the right to identity as the right to a gender identity, i.e. to have a recognized name, publicly recorded and reported on IDs, which is aligned with one’s gender (this right was granted to trans people in Argentina in 2012). In its Facebook group, the Archivo asked members for their own names after gender transitioning and nicknames, as well as the names and nicknames of their friends and loved ones. More than 600 were collected and used for creating lists for different occasions, purposes, campaigns and media – including the 2020 book. The names and nicknames are preceded by a “la”, the Spanish feminine for “the”. The continuous repetition of the “la” gives the list a musicality, while the continuous use of the feminine article genders the practice of listing names.

Foldout flap from Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina.

The playful nature of the nicknames, the pink lettering and the musicality of the list, queer a commemorative practice that is mainly used for mourning. The practice is subverted by a celebratory tone transforming it into a poetic list. These names celebrate, perform and claim a right to gender identity, to visibility and to a public memory. They allow for the possibility of choosing one’s own name and of being named by others in a way that chimes with one’s own identity in both the private and the public sphere.

The case of the Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina epitomizes how memory and its practices and genres are crucial tools in activism. As a bricoleur of memory, the Archivo de la Memoria Trans Argentina adopt genres and practices for remembering (as we have seen in the specific example of naming), borrowed from other traditions and social groups, and creatively transform them in order to shape their own collective memories. Pictures and names, by making individual trans lives visible, play a central role in visually materializing a social group so that they can act and speak publicly. To investigate how LGBTQ activists do this through archives and related publications – as well as through commemorative marches and the use of memorial, monument and public spaces – is an issue that scholars still need to address within a memory studies agenda.